Why Young People Struggle to Enter Aerospace Careers

Industry leaders warn that weak outreach, poor guidance, and systemic barriers are preventing the UK from developing the next generation of aviation talent

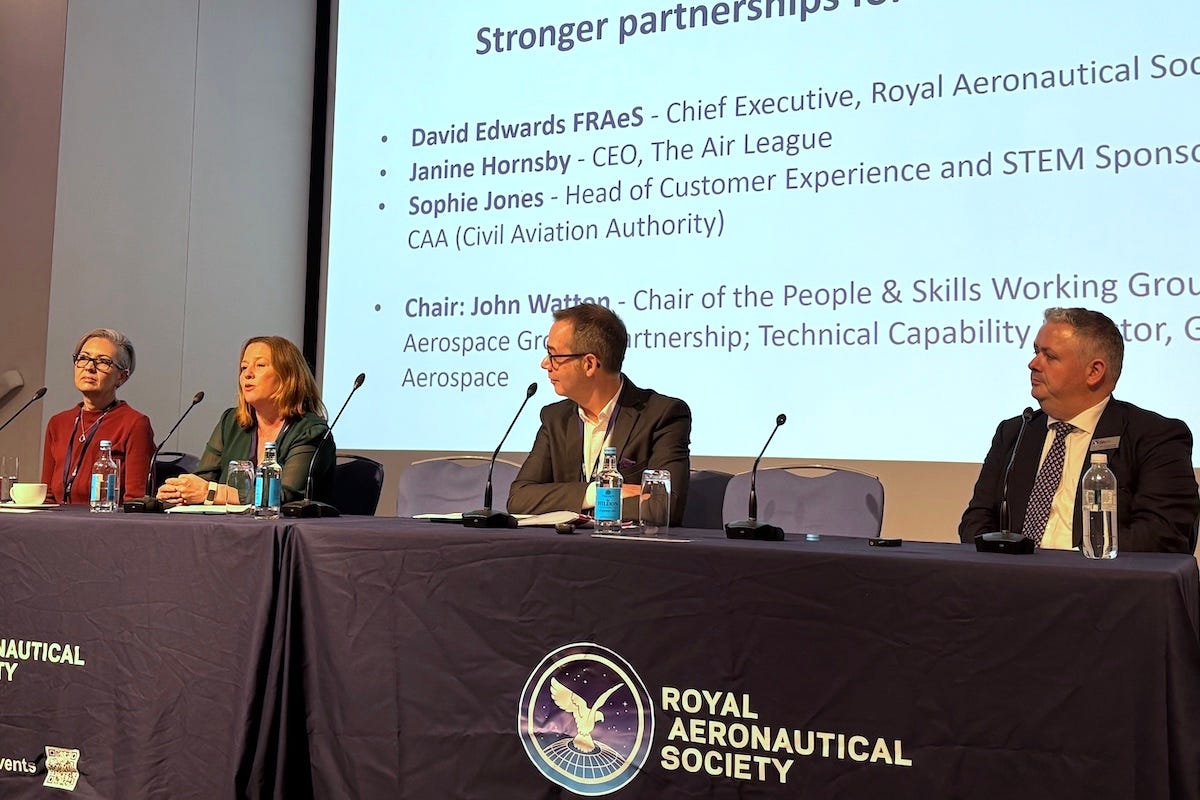

Collaboration between the aerospace sector and the education community must deepen if the UK is to develop the skilled workforce needed for the next era of flight innovation. This was the resounding message from senior figures at the Royal Aeronautical Society’s President’s Conference on People in Aerospace in London.

Speakers agreed that, while aerospace remains one of Britain’s most advanced industries, sustaining a future-ready talent pipeline is critical. The panel warned that the country lacks sufficient alignment between government, academia, and industry to meet its long-term workforce ambitions in emerging areas such as hydrogen propulsion, data analytics, and robotics.

John Watton, Technical Capability Director at GKN Aerospace and Chair of the People & Skills Working Group at the Aerospace Growth Partnership, said the industry’s current training frameworks must evolve to meet the complex skills demanded by future programmes.

“We need lots of people with varied skill sets… proficiency levels will increase around AI, data analytics, and robotics. But it’s clear we do not have a pipeline to meet our national objectives,” he cautioned.

He attributed this shortage to several factors:

Fragmented coordination among industry, government, and academia yields inconsistent skill development strategies.

Rapidly changing technological needs, such as hydrogen propulsion, urban air mobility, and AI integration, are outpacing educational adaptation.

Limited early exposure to STEM and aerospace careers among schoolchildren.

A shortfall in practical apprenticeships and digital upskilling programs is needed for next-generation aerospace roles.

Sophie Jones, Head of Customer Experience and STEM Sponsor at the UK Civil Aviation Authority, stressed that outreach must begin in primary education.

“Research tells us that children are curious about their careers at five to seven years old. Primary school is key for us to encourage those choices,” she said. She added that regulators, manufacturers, and educators “can’t do this alone,” urging unified action to provide consistent engagement across all stages of education.

“One of us as individuals or organisations can’t do this alone,” Jones said. “This is very much about us working together to fix the problem collectively.”

Rethinking Outreach and Curriculum

The discussion formed part of the Stronger Partnerships for Future Talent panel held during the Royal Aeronautical Society’s President’s Conference on October 7, 2025. The event brought together key leaders from across aerospace, education, and government to explore how coordinated partnerships can strengthen the UK’s long-term skills base.

Royal Aeronautical Society Chief Executive David Edwards called for a “complete rethink” of how aerospace engages with schools.

“We do school outreach because that’s what we’ve always done. Maybe it’s time for a rethink on how we do our inspirational moments,” he said.

Edwards observed that the sector’s fragmented outreach programmes risked diluting their impact. “Wouldn’t it be great if we all delivered the same thing so that when the CAA, the Air League, or we go into schools, aerospace becomes a consistent theme throughout a child’s education?”

He noted that while the sector spends millions annually on educational outreach, global competitors invest vastly more.

“If you do the maths, we collectively spend maybe £3 million a year. Google spends billions on outreach. How do we make our limited funding more impactful?” he asked.

Janine Hornsby, Chief Executive of the Air League, underscored the importance of industry-backed teaching resources that connect classroom theory with real-world applications.

“Teachers aren’t industry experts, so they need our help,” she said. “If industry can show how Ohm’s law links to electronic engineering and design, it suddenly contextualises what students are learning in class.”

Hornsby warned, too, of the human consequences of digital isolation. “The percentage of young people in relationships with AI bots is staggering. We must focus on teamwork, critical thinking, and emotional intelligence. These people skills are equally, if not more, important.”

Barriers to Entry

Panelists discussed a range of obstacles preventing children and young people from entering the aerospace sector. Edwards said that a lack of exposure at the primary school level is a critical weakness: “Every teacher I interact with wants to be involved; we just need to deliver to them when they’re receptive.”

Many teachers have limited contact with the industry, even when schools are situated near airports. The result is that children grow up without seeing aerospace as a viable career option.

Jones added that misconceptions are also a problem.

“Most young people think aerospace is just for engineers and pilots,” she said. “They don’t realise there’s a whole spectrum of other jobs, and many believe they’re not clever enough because they think it’s all about maths and physics.”

Hornsby highlighted hidden barriers, including financial and cultural challenges.

“One young man nearly lost a pilot opportunity because he couldn’t swim—a requirement for many airlines. Eighty-five percent of ethnic minority young people can’t swim,” she said. “There are cultural concerns for young Muslim women entering male-dominated environments. We need to understand these barriers better.”

The panel emphasized the importance of educating parents, many of whom are unaware of career paths in the aerospace industry.

“Parents are even more influential than teachers,” said Hornsby. “Bringing them into events and showing them their child’s progress can change perceptions.”

Jones suggested that family-oriented outreach, from air shows to weekend workshops, could help bridge the generational knowledge gap.

The panel recognised the challenge of geographic inequality. Edwards illustrated this with an example from his home village in Wales, where the local primary school had not seen a single industry visit despite being next to an airfield. Such rural and remote schools rarely receive industry engagement, leaving many children with no exposure to aerospace careers.

Hornsby warned of a growing mismatch between university graduates and apprenticeship pathways. Many degree holders in aeronautical engineering struggle to find placements because employers now prioritise degree apprenticeships. This misalignment leaves qualified candidates unable to gain industry experience, highlighting the need for coordinated education-to-employment reform.

Bridging the Skills Gap

Speakers agreed that the skills challenge extends beyond recruitment to fundamental training. Jones said many applicants lack both technical and soft skills.

“Interview prep, corporate etiquette, and communication are often missing,” she said. “We assume kids have support networks at home to prepare them, but many don’t. We need to fill that gap.”

Edwards added that despite good intentions, duplication of effort remains a chronic problem. “We’ve all got brilliant ideas, but we need to stop doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different response. We must work together in a much more brilliant way.”

Hornsby pointed out that schools often misdirect students.

“A lot of teachers send aspiring aircraft maintenance technicians to university instead of apprenticeships,” she explained. “They think they’re helping, but it can actually overqualify them for entry-level roles. We need to ensure teachers understand all the routes into aerospace.”

Speakers discussed how better career guidance and teacher training could prevent talent loss to other industries, such as motorsport or banking.

“We’re losing far more engineers than we realise,” Hornsby warned. “We have the people; we just don’t have the right routes for them.”

Towards a Unified Strategy

When asked how the ideal aerospace talent ecosystem might look, Edwards was blunt: “It wouldn’t look like this.” He criticised the proliferation of disconnected initiatives—“a new charity or programme every month”—and called for consolidation. “If we all understood that working outside this collaborative framework won’t have the desired effect, we could make real progress.”

Jones agreed that the challenge is both global and national. “This isn’t just a UK problem—every country is facing it. We need collaboration on a global scale to share best practices and ideas.”

Hornsby issued a stark warning: “This is not a new problem. We’ve been talking about it for 20 years. If we don’t act now, the industry won’t be here.”

Edwards concluded with a reminder from history. “Back in 1999, the Society published a paper predicting exactly the skills crisis we face today. It said this wasn’t a government problem to fix but a sector problem to resolve—and that’s still true.”

The panel agreed that government initiatives such as Skills England and the UK’s new industrial strategy could provide a framework for coordination—but only if industry acts decisively.

“If the opportunity is acted upon, there is real potential,” said Jones. “We’ve seen growth in apprenticeships, but we need to roll things out properly. We must stop talking and deliver.”

As the aerospace sector navigates the twin transitions of sustainability and digitalisation, its long-term competitiveness will depend not only on technology but on people. The message from the Royal Aeronautical Society’s conference was clear: to secure the skies of tomorrow, the UK must unite classrooms, companies, and communities today.