PQShield Flags Supply Chain Gridlock in Quantum Security Migration

While cryptographic standards progress, stalled vendor engagement is delaying industry-wide post-quantum transitions

Quantum computing's looming threat to current cryptographic systems has forced the cybersecurity world to brace for a tectonic shift. Yet as security leaders begin their migration to post-quantum cryptography (PQC), a formidable barrier persists: the supply chain.

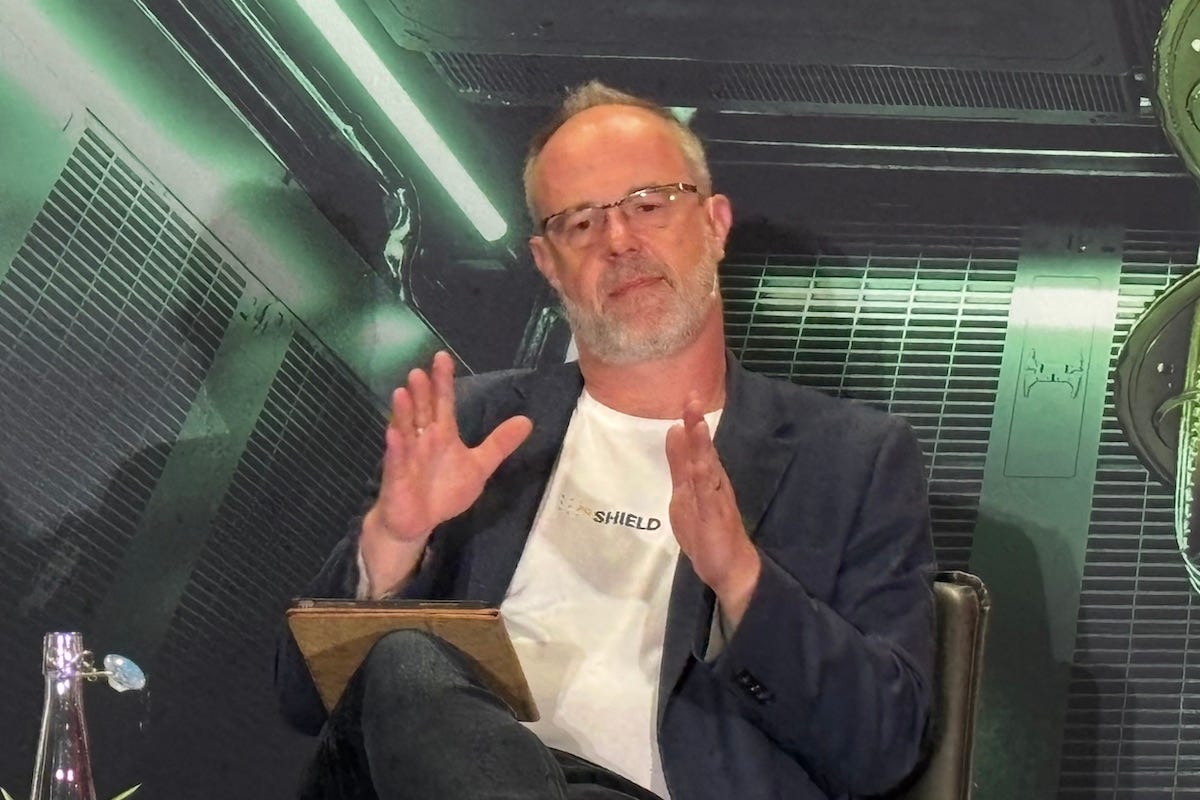

This is not a matter of technology readiness, but of communication inertia. Ben Packman, Chief Strategy Officer at PQShield, said about 80% of the cryptographic infrastructure within a given enterprise lies outside its direct control, embedded in third-party vendors and service providers. That is where the migration stalls.

"Most CISOs [Chief Information Security Officers] do not understand cryptography," he said. "So crypto discovery becomes a bit of a black hole."

He noted official standards and regulatory guidance now frame the urgency.

"We have a pretty recognized five to 10-year window," he said. "This isn't just theory—it's backed by laws in the US and works here in the UK."

The real-world consequences are already emerging. A large U.S.-based infrastructure provider nearly locked itself into a 10-year contract for non-compliant equipment.

"They were about to order a very large number of networks—eye-watering amounts of money involved," he said. "But neither their vendors nor vendors' vendors mentioned PQC."

He said that the purchase would have embedded legacy cryptography into the company's infrastructure and made it almost impossible to upgrade around 10% of their systems for a decade.

He added, "That highlights the power of everyone needing to be a bit more transparent."

A Strategic Pivot: Vendor-First Discovery

Speaking at Commercializing Quantum Global 2025 in London on May 14, Packman proposed a practical alternative to a complete cryptographic inventory: start with the data.

"Find the data that you care about most—data with a long enough half-life to matter," he advised. "Then, map all the vendors that touch it. It won’t be perfect, but it gives you a quick and useful start."

Most organizations identify 50 to 60 vendors this way. Some, he said, may be part of ongoing SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) contracts that can be relatively agile. Others, however, are deeply embedded in legacy infrastructure.

"You can switch a CRM (customer relationship management) vendor with fewer headaches, especially when you're paying on a monthly basis. There's competition and leverage," Packman said. "But it's the long-term contracts—the vendors who have no commercial or legal motivation to modernize—that are the problem."

Packman advised segmenting vendors by flexibility. Those with decade-long infrastructure deals may be the slowest to adapt.

"You're going to need a contract variation," he warned. "And we all know what contract variations code for: more money."

He also flagged the danger of oversimplified compliance questionnaires. "'Do you do PQC?' is an easy box to tick," he said. "But a firewall needs PQC in multiple places. Doing one isn’t good enough."

Understanding the specific points in a product's architecture where PQC must be applied is critical. For instance, a single network device may need quantum-safe protections in its secure boot process, application layer, anti-counterfeiting chip, and LAN card.

He added that many vendors will try to meet minimum standards to win contracts without delivering comprehensive security. "You have to ask the right questions. Just checking a box isn’t the same as being protected."

Mobilizing Internal Stakeholders

Packman acknowledged that many CISOs struggle to build boardroom support. The main issue? How the problem is presented.

"They're going in saying, 'We've got this quantum problem,' and the board asks, 'When?' The answer is vague—maybe soon, maybe later. So the board says, 'Come back when you know.'"

He suggested a more concrete approach: Tell them, "We have five to 10 years. These are the deadlines. Here's our vendor analysis: 20% done, 50% in progress. We need help closing the gap."

This approach reframes the issue from a distant theoretical risk to an active, ongoing project with milestones. Board members are more likely to respond to action plans than to ambiguity.

He also pointed out the structural challenges: "PQC migration is a 'two-CEO problem'. The CEO who starts it may not be around to finish it. But leadership still needs to commit."

The long timelines for quantum migration pose both a budgetary and strategic challenge. As boards focus on quarterly outcomes, Packman said it's crucial to demonstrate measurable progress.

"Go into the boardroom with results, not just forecasts," he advised. "If you can say you've already de-risked 20% of the vendor base, that changes the tone of the conversation."

Packman emphasized legal alignment as well. "If you want to sell to the federal government, you need to comply. If not, you can't even bid. It's not a luxury. It's a business need."

Legal and compliance teams, he added, can become key allies. As regulations tighten, especially in the U.S. and EU, companies will find themselves forced into compliance whether they are ready or not.

The role of national governments in driving standards is growing. He noted that NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) has laid out timelines that will make current cryptography obsolete. "By 2035, RSA (the Rivest–Shamir–Adleman cryptosystem) won't be allowed in Common Criteria. Others will follow."

Time Is Running Out—Quietly

Packman rejected the notion of a fixed deadline.

"There isn't any such thing as Q-Day," he said. "Nobody's going to announce they can break cryptography. They'll just use it."

He confirmed that adversaries are already stockpiling sensitive data. "Are they harvesting data? Categorically yes. Hackers always have. Storage is cheap. They’re preparing for when they can decrypt it."

This "harvest now, decrypt later" approach poses a severe risk for sensitive government communications, defense data, and long-cycle intellectual property. These could be breached years from now, unless encrypted today with quantum-safe methods.

Despite these risks, he remains cautiously optimistic. "Momentum breeds momentum. If we can build that—and a bit of transparency—we've got a real chance."

As the quantum threat edges closer to reality, it is not algorithms that pose the biggest risk, but human delay. The time to act is now.