ESA Seeks Budget Hike to Secure Enceladus Mission Under Voyage 2050

Europe’s space science ambitions hinge on modest funding increase to pursue life-detection missions and safeguard flagship observatories

A new era of European space exploration is at stake as the European Space Agency prepares its proposal for the 2025 ministerial conference. At the heart of the proposal is a modest budget increase intended to preserve scientific momentum across multiple fronts—most notably the launch of ESA’s next flagship planetary science mission to Saturn’s icy moon, Enceladus.

This is no ordinary target. Identified as the most promising destination in ESA’s Voyage 2050 strategy, Enceladus offers a rare opportunity to search for signs of life beyond Earth. Its subsurface ocean, active geysers, and complex chemistry have made it a prime candidate for habitability studies.

To meet mission timelines driven by celestial mechanics, ESA must initiate technology development now to enable a launch in the early 2040s and a landing in 2052. The agency is seeking financial support to begin this work before the end of the year.

“The destination that’s been selected is Enceladus, and we now seek the funding to start that technology development, because we have a cosmic deadline to meet,” said Carole Mundell, ESA’s Director of Science. “We know when we have to land.”

The upcoming proposal represents what Mundell described as a “very modest uplift on the current level of resources.” She added that the plan would enable ESA to complete all previously approved missions while initiating critical technology work for future exploration.

She made the comments in an interview with TechJournal.uk on the sidelines of the UK Space Conference 2025 in Manchester on July 17, 2025.

Strategic science at scale

Appointed by ESA in 2023, Mundell brings a distinctive combination of scientific, diplomatic, and leadership experience. She previously served as the UK government’s Chief Scientific Adviser at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and was the founding Head of Astrophysics at the University of Bath. Her academic career includes pioneering work in extragalactic astrophysics, and she has published more than 170 peer-reviewed papers.

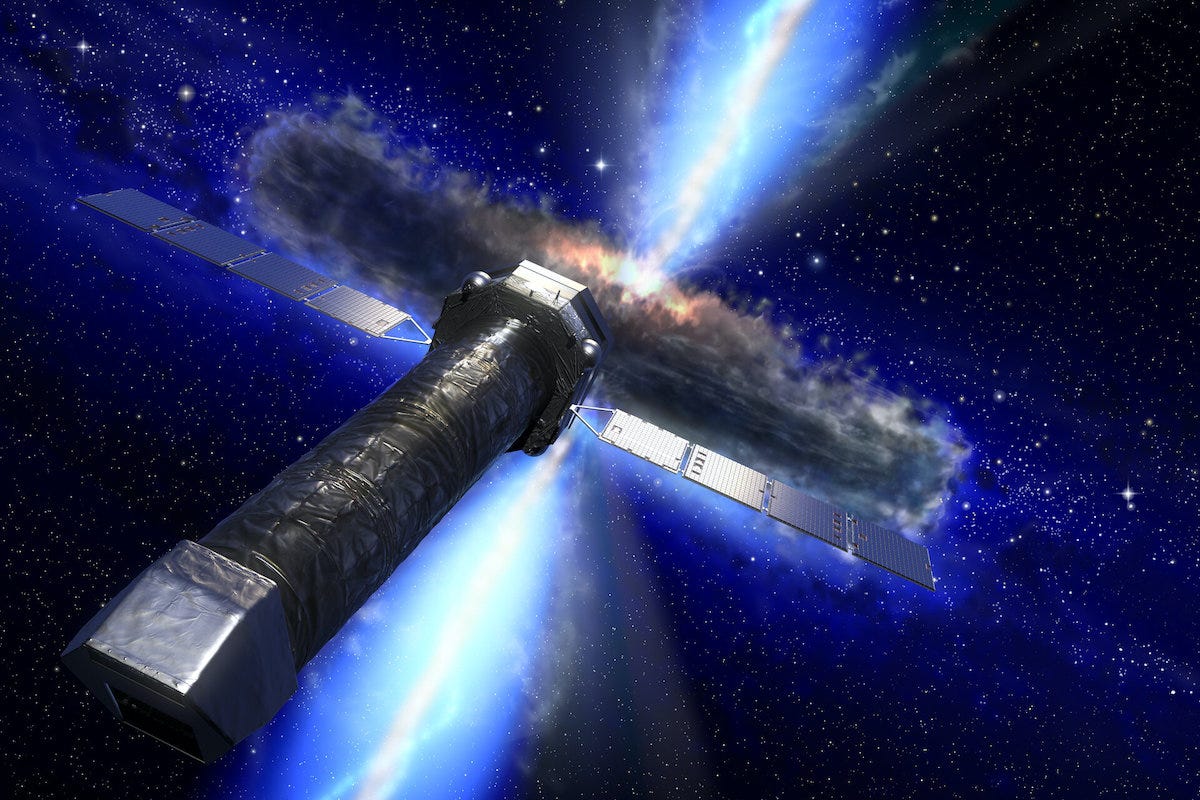

Now at the helm of ESA’s science program, she oversees a portfolio that spans flagship missions, fast-track projects, and collaborative contributions. One such mission is NewAthena, a large-class X-ray observatory scheduled for launch in 2037. It demonstrates the challenges inherent in L-class missions—projects too complex for any one nation and developed through joint, long-term European commitment.

“The L-class missions are ones that no single country can do. For that type of mission, everybody comes together to do that,” she said.

The fourth L-class mission under Voyage 2050, now designated L4, will focus on Enceladus.

Mundell said the decision followed an extensive period of technical and scientific assessment and was guided by a fixed launch window tied to the moon’s orbital conditions.

Budget contrasts across the Atlantic

ESA’s current budget stands at €7.68 billion ($8.99 billion) for 2025, a slight decrease from €7.79 billion in 2024. In contrast, NASA’s budget for the fiscal year 2025 is $25.38 billion, compared with $24.875 billion a year earlier.

ESA is working to align its constrained funding model with long-term mission goals.

Unlike most ESA programs, the science budget is mandatory; each of the 23 member states contributes according to its gross national product. That means all countries must agree unanimously to any proposed increase. Mundell described the current proposal as a carefully modelled financial envelope that respects national constraints while delivering cross-European benefits.

ESA’s Missions in Development

ESA's current mission pipeline spans planetary science, astrophysics, and exoplanet exploration. Each is at a different stage of readiness:

SMILE (2026) - A mission to study solar wind and Earth’s magnetic field interaction using X-ray imaging, particularly during the current solar maximum.

Plato (2026)- A mission to discover and characterise Earth-like exoplanets in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars using 26 telescopes.

Martian Moons eXploration – MMX (2026) - Led by JAXA with ESA contributions, MMX will land on Phobos and return a sample to Earth, offering insights into Mars’s formation history.

Roman (2026) - A NASA-led, ESA-involved project, this wide-field infrared telescope will study dark energy and exoplanets across large cosmic volumes.

Comet Interceptor (2029) - A fast-class mission that will intercept a pristine comet and deploy two probes to study it from multiple angles.

Ariel (2029) - This mission will observe the atmospheres of 1,000 exoplanets, offering insights into their chemical composition and climate systems.

Arrakihs (2030) - A fast-track astrophysics mission to test predictions of dark matter models by studying faint structures in galactic halos.

Envision (2031) - A comprehensive investigation of Venus’s atmosphere, surface, and interior, designed to reveal why its evolution diverged so sharply from Earth’s.

Lisa (2035) - A trio of spacecraft forming the first space-based gravitational wave observatory, designed to detect cosmic events like black hole mergers.

NewAthena (2037) - An X-ray observatory restructured to reduce costs while preserving scientific capabilities to study hot gas and large-scale cosmic structures.

ESA’s science program is structured around multi-tiered mission classes. L-class missions, such as Enceladus and NewAthena, span decades and rely on steady political and financial support. M-class missions, such as Euclid, follow a more streamlined path and are selected from highly competitive proposals.

ESA is also evaluating “mini-F” missions—smaller, less expensive projects that can leverage new technologies or address emerging scientific questions on shorter timescales.

“The way we prioritise is always scientifically,” said Mundell. “It’s competitive in scientific peer review. The industrial contracts are competitive with industry as well.”

This competitive framework allows ESA to maintain quality and credibility, while the agency’s triennial planning cycle provides long-term visibility. Mundell explained that the program functions like a rolling 10-year business plan, providing certainty to industry stakeholders and research institutions.

Investing now for missions decades away

The ESA Ministerial Council meeting, scheduled for November in Bremen, Germany, will be pivotal. This high-level summit, held every three years, brings together government ministers from ESA’s 23 member states to decide on future space programs and associated funding.

At the 2022 meeting in Paris, ministers approved €16.9 billion in funding across ESA’s programmatic landscape. Bremen 2025 is now just four months away.

Mundell said she and her team have spent over two years working closely with all member states to build consensus around the current funding proposal. The aim is not just to deliver existing missions but to lay the groundwork for future planetary science at a time when technical schedules, launch constraints, and public expectations are all converging.

She emphasised that the budget proposal is designed to be efficient, competitive, and forward-looking.

“I put all of that together, and that sets the envelope on the budget and the evolution for the future,” she said.

With Enceladus in sight—and the solar system’s clock ticking—the decisions made in Bremen may determine whether ESA continues to lead in deep-space science or misses a generational opportunity.